Gustav Klimt was born on 14th July 1862 in Vienna into a lower middle-class family of Moravian origin. His father, Ernst Klimt, worked as an engraver and goldsmith, earning very little, meaning that as well as spending his childhood in relative poverty the artist would have to support his family financially throughout his life.

Gustav Klimt was born on 14th July 1862 in Vienna into a lower middle-class family of Moravian origin. His father, Ernst Klimt, worked as an engraver and goldsmith, earning very little, meaning that as well as spending his childhood in relative poverty the artist would have to support his family financially throughout his life.

In 1876, Klimt was awarded a scholarship to the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts, where he studied until 1883, and received training as an architectural painter. He revered the foremost history painter of the time, Hans Makart and readily accepted the principles of his conservative training. In 1877 his brother Ernst, who, like his father, would become an engraver, also enrolled in the school. The two brothers began working together alongside friend Franz Matsch and by 1880 they had received numerous commissions as a team which they called the Company of Artists as well as helping their teacher to paint murals in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

After finishing his studies, Klimt opened a studio together with Matsch and Ernst Klimt. The trio specialized in interior decoration, particularly theatres. Already by the 1880s, they were renowned for their skill and decorated theatres throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where much of their work can still be seen. In 1885, they were commissioned to decorate the Empress Elizabeth’s country retreat, the Villa Hermes near Vienna (Midsummer Night’s Dream). In 1886, the painters were asked to decorate the Viennese Burgtheater, effectively recognizing them as the foremost of decorators of Austria. Works that Klimt painted for this project include The Cart of Thespis, The Altars of Dionysos and Apollo and The Theater at Taormina, as well as scenes from the Shakespearean Globe Theater. At the completion of the work in 1888, the painters were awarded the Golden Service Cross (Verdienstkreuz), and Klimt was commissioned to paint the Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater, the work that would bring him to the height of his fame. This painting, with its almost photographic accuracy is considered one of the greatest achievements in Naturalist painting. As a result, Klimt was awarded the Emperor’s Prize and became a fashionable portraitist, as well as the leading artist of his day. Paradoxically, it was at this point, with a fabulous career as a classicist painter unfolding before him, that Klimt began turning towards the radical new styles of Art Noveau.

In the coming few years, the artistic trio fell apart. Franz Matsch wanted to branch out into portrait painting, which he did with some success. Meanwhile, Gustav Klimt’s changing style made it impossible for them to work together on any project. Furthermore his brother died in 1892, shortly after the death of their father. Struck by this double tragedy, Gustav retreated from public life, focusing on experimentation and the study of contemporary styles of art, as well as historical styles that were overlooked within the establishment, such as Japanese, Chinese, Ancient Egyptian and Mycenaean art. In 1893, he began work on his last public commission: the paintings Philosophy, Medicine and Jurisprudence, for the University of Vienna. The three would only be completed in the early 1900s, and they would be criticized severely for their radical style and what was, according to the mores of the time, lewdness. Unfortunately, the paintings were destroyed during the Second World War and only black-and-white reproductions of them remain.

The painter was not alone in his opposition to the Austrian artistic establishment of the time. In 1897, he, together with forty other notable Viennese artists, resigned from the Academy of Arts and founded the Union of Austrian Painters, more commonly known as the Secession. Klimt was immediately elected president. While the Union had no clearly defined goals or support for particular styles, it was against the classicist establishment, which it found to be oppressive.

In 1902, Klimt finished the Beethoven Frieze for XIV Vienna Secessionist Exhibition, which was intended to be a celebration of the composer and featured a monumental, polychromed sculpture by Max Klinger. Meant for the exhibition only, the frieze was painted directly on the walls with light materials. After the exhibition the painting was preserved, although it did not go on display until 1986.

During this period Klimt did not confine himself to public commissions. Beginning in the late 1890s he took annual summer holidays with the Flöge family on the shores of Attersee and painted many of his landscapes there. Klimt was largely interested in painting figures; these works constitute the only genre aside from figure-painting which seriously interested Klimt. Klimt’s Attersee paintings are of a number and quality so as to merit a separate appreciation. Formally, the landscapes are characterized by the same refinement of design and emphatic patterning as the figural pieces. Deep space in the Attersee works is so efficiently flattened to a single plane, it is believed that Klimt painted them while looking through a telescope.

Klimt’s ‘Golden Phase’ was marked by positive critical reaction and success. Many of his paintings from this period used gold leaf; the prominent use of gold can first be traced back to Pallas Athene, (1898) and Judith I (1901), although the works most popularly associated with this period are Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) and The Kiss (1907-1908). Klimt travelled little but trips to Venice and Ravenna, both famous for their beautiful mosaics, most likely inspired his gold technique and his Byzantine imagery. In 1904, he collaborated with other artists on the lavish Palais Stoclet, the home of a wealthy Belgian industrialist, which was one of the grandest monuments of the Art Nouveau age. Klimt’s contributions to the dining room, including both Fulfillment and Expectation, were some of his finest decorative work, and as he publicly stated, “probably the ultimate stage of my development of ornament.” Between 1907 and 1909, Klimt painted five canvases of society women wrapped in fur. His apparent love of costume is expressed in the many photographs of Flöge modelling clothing he designed.

As he worked and relaxed in his home, Klimt normally wore sandals and a long robe with no undergarments. His simple life was somewhat cloistered, devoted to his art and family and little else except the Secessionist Movement, and he avoided café society and other artists socially. Klimt’s fame usually brought patrons to his door, and he could afford to be highly selective. His painting method was very deliberate and painstaking at times and he required lengthy sittings by his subjects.

By 1910, Klimt had moved past his Golden Style. One of his last pictures in that style was Death and Life (1908-1910). In 1911, the painting was shown at the International Exhibition in Rome, where it won first place. However, the artist was dissatisfied with the work, and in 1912, he changed the background from gold to blue.

In 1915 his mother Anna died. Klimt died three years later in Vienna on February 6, 1918, having suffered a stroke and pneumonia. He was buried at the Hietzing Cemetery in Vienna, leaving numerous works unfinished.

Klimt’s paintings have brought some of the highest prices recorded for individual works of art. In 2006, the 1907 portrait, Adele Bloch-Bauer I, was purchased for the Neue Galerie in New York by Ronald Lauder for a reported USD $135 million, surpassing Picasso’s 1905 Boy With a Pipe (sold May 5, 2004 for $104 million), as the highest reported price ever paid for a painting.

Klimt’s work is often distinguished by elegant gold or coloured decoration, spirals and swirls, and phallic shapes used to conceal the more erotic positions of the drawings upon which many of his paintings are based. This can be seen in Judith I (1901), and in The Kiss (1907-1908), and especially in Danaë (1907). One of the most common themes Klimt used was that of the dominant woman, the femme fatale.

Art historians note an eclectic range of influences contributing to Klimt’s distinct style, including Egyptian, Minoan, Classical Greek, and Byzantine inspirations. Klimt was also inspired by the engravings of Albrecht Dürer, late medieval European painting, and Japanese Rimpa school. His mature works are characterized by a rejection of earlier naturalistic styles, and make use of symbols or symbolic elements to convey psychological ideas and emphasize the freedom of art from traditional culture.

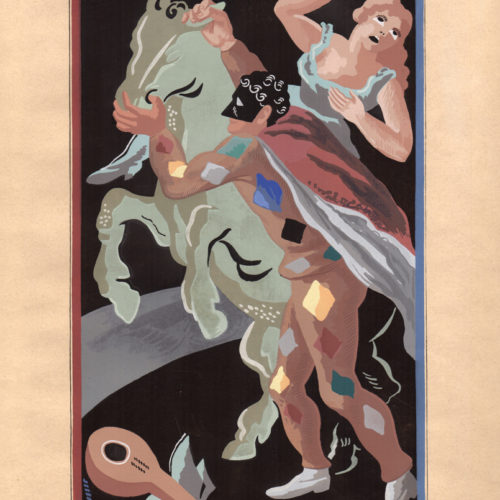

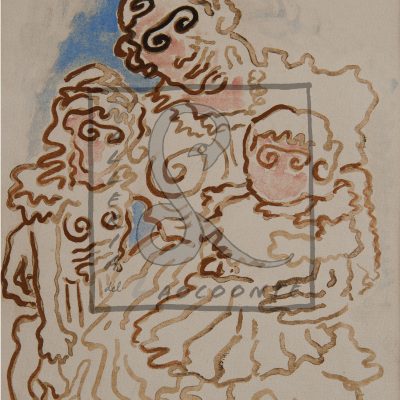

Umberto Brunelleschi was born in Monterulo in 1879. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence. He moved to Paris in 1900 where he found success as a painter, illustrator and designer.

Umberto Brunelleschi was born in Monterulo in 1879. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence. He moved to Paris in 1900 where he found success as a painter, illustrator and designer.

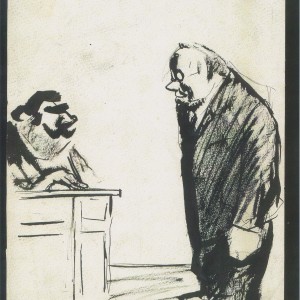

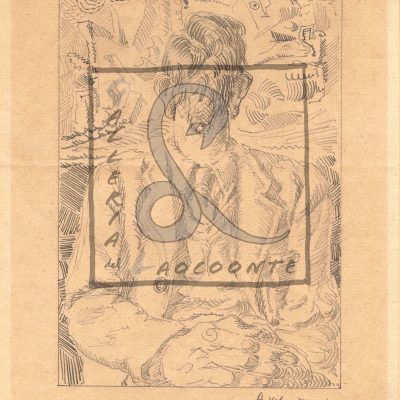

Alberto Ziveri was born in Rome in 1908. He was a modernist painter of the Scuola Romana, an art movement which was defined by a group of Expressionist painters active in Rome between 1928 and 1945. Ziveri painted urban landscapes and realist narrative scenes. He used chiaroscuro painting techniques to explore everyday subject matter, which ranged from depicting piazzas and tram stops to the interior scenes of brothels. In 1943, Ziveri won the IV Premio Quadriennale di Roma art award, and in 1989 the literary prize Premio Viareggio-Rèpaci. He died in Rome in 1990.

Alberto Ziveri was born in Rome in 1908. He was a modernist painter of the Scuola Romana, an art movement which was defined by a group of Expressionist painters active in Rome between 1928 and 1945. Ziveri painted urban landscapes and realist narrative scenes. He used chiaroscuro painting techniques to explore everyday subject matter, which ranged from depicting piazzas and tram stops to the interior scenes of brothels. In 1943, Ziveri won the IV Premio Quadriennale di Roma art award, and in 1989 the literary prize Premio Viareggio-Rèpaci. He died in Rome in 1990.

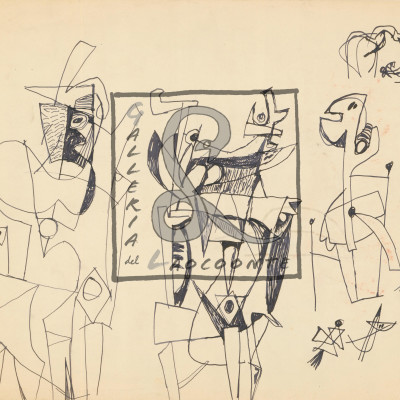

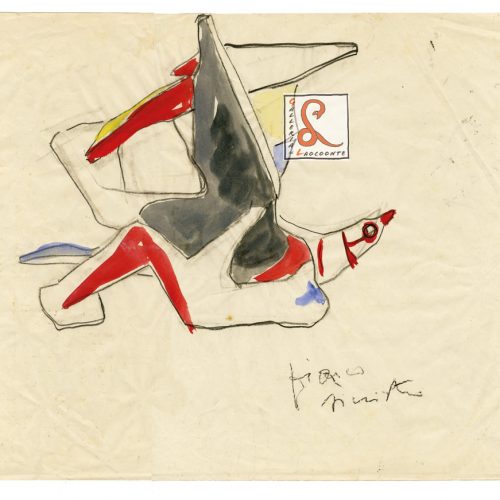

Fortunato Depero was born on 30th March, 1892, in Fondo, Italy. His education began at Scuola Reale Elisabettina in Rovereto, Italy, where he learned fine art techniques alongside those for the applied arts. In 1910 he began a job as a marble worker’s apprentice to further his artistic development before discovering the Italian journal Lacerba in 1913, which inspired his movement towards futurism. Although Depero’s career began as a fine artist he was to find significant success following his development into the commercial art scene, ultimately becoming one of the most successful futurist graphic designers.

Fortunato Depero was born on 30th March, 1892, in Fondo, Italy. His education began at Scuola Reale Elisabettina in Rovereto, Italy, where he learned fine art techniques alongside those for the applied arts. In 1910 he began a job as a marble worker’s apprentice to further his artistic development before discovering the Italian journal Lacerba in 1913, which inspired his movement towards futurism. Although Depero’s career began as a fine artist he was to find significant success following his development into the commercial art scene, ultimately becoming one of the most successful futurist graphic designers.

Gustav Klimt was born on 14

Gustav Klimt was born on 14

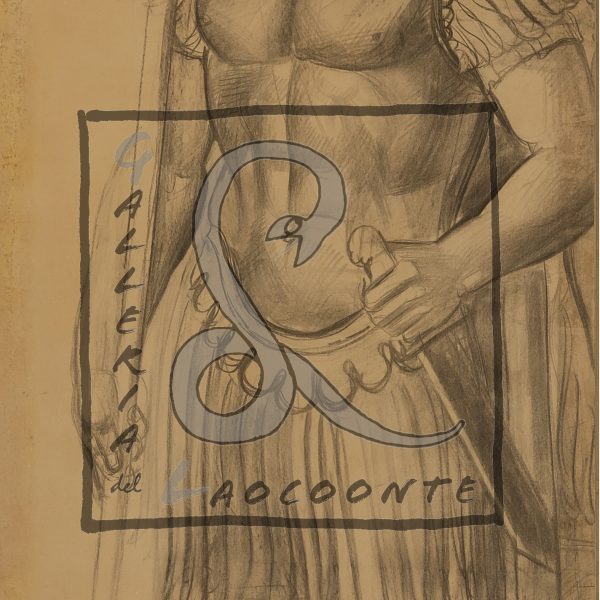

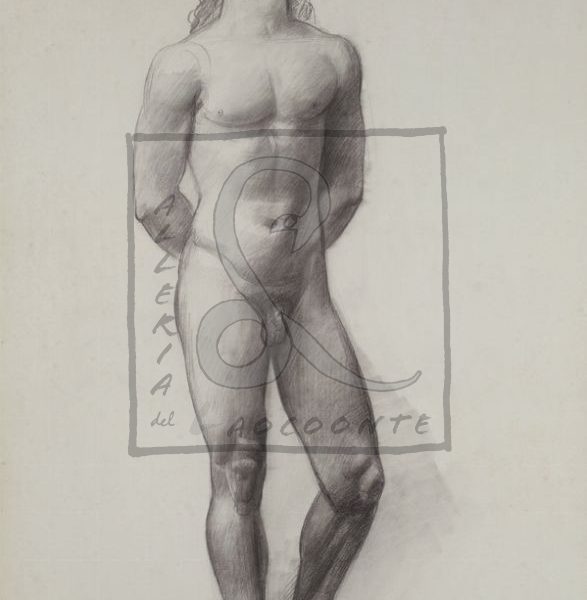

Mario Sironi was born in Sassari on 12th May 1885. He was the second of six children. Following the untimely death of his father, who left him orphaned at the age of thirteen, he moved to Rome where he later studied. His adolescence was spent in a house on via di Porta Salaria, not far from Villa Borghese. It was an adolescence marked not only by the charm of the Eternal City but also by a great passion for reading (Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heine, Leopardi, the French novelists) and the study of music, especially Wagner who played the piano with his older sister Cristina. In 1902 he began to study engineering but a year later, encouraged by the positive opinion of the old sculptor Ximenes, he left and devoted himself to painting. It was whilst attending Scuola Libera del Nudo in via Ripetta that he met and studied with Giacomo Balla as well and becoming close friends with Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini.

Mario Sironi was born in Sassari on 12th May 1885. He was the second of six children. Following the untimely death of his father, who left him orphaned at the age of thirteen, he moved to Rome where he later studied. His adolescence was spent in a house on via di Porta Salaria, not far from Villa Borghese. It was an adolescence marked not only by the charm of the Eternal City but also by a great passion for reading (Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heine, Leopardi, the French novelists) and the study of music, especially Wagner who played the piano with his older sister Cristina. In 1902 he began to study engineering but a year later, encouraged by the positive opinion of the old sculptor Ximenes, he left and devoted himself to painting. It was whilst attending Scuola Libera del Nudo in via Ripetta that he met and studied with Giacomo Balla as well and becoming close friends with Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini.

LIFE OF LEONCILLO

LIFE OF LEONCILLO

Gino Severini was born in Cortona, a hilltop town positioned within the famous landscapes of Tuscany, on 7th April, 1883.

Gino Severini was born in Cortona, a hilltop town positioned within the famous landscapes of Tuscany, on 7th April, 1883.

Giacomo Balla was born in Turin on July 18th 1871.

Giacomo Balla was born in Turin on July 18th 1871.

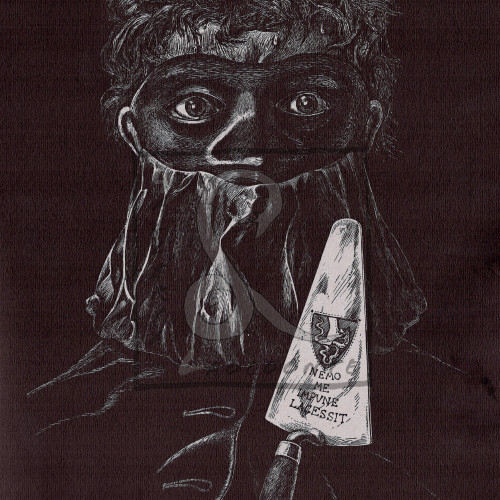

Duilio Cambellotti was born in Rome in 1876 and although he learned his first artistic skills in the workshop of his father Antonio from an early age his initial training was in accountancy, from which he graduated while studying art independently.

Duilio Cambellotti was born in Rome in 1876 and although he learned his first artistic skills in the workshop of his father Antonio from an early age his initial training was in accountancy, from which he graduated while studying art independently.

Afro Basaldella was born in Udine on 4th March 1912.

Afro Basaldella was born in Udine on 4th March 1912.